An Interior of Alcazar, Seville

Collections

The Haggin Museum is the steward of many cultural treasures, but none combine beauty with functionality as well as its collection of baskets created by Native California women, recognized as the finest basket weavers in the world. Examples of gathering, storage, cooking, gift, and baskets from various tribal groups from throughout the State reflect the diversity of California’s original inhabitants.

An indispensable aspect of Native Californians’ everyday lives, the baskets on display illustrate the different techniques and designs employed by our State’s various tribal groups, including Yokuts, Miwok, Pomo, and Washoe. In addition, while baskets were woven in every region of California, and the raw materials utilized by Native weavers depended upon each group’s environment, some common fibers included bear grass, willow, redbud, maiden hair, and bracken fern. Although the baskets in the museum’s collection were made many decades ago, they continue to serve as a tangible link between today’s Native people and their cultural heritage.

Stephens Brothers—one of the most respected names in pleasure craft design—began in 1902 when brothers Thod and Roy Stephens launched their first boat into the Stockton Channel. Initially, they built work boats and launches that were instrumental in the development of agriculture throughout the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta region. By the mid-1920s, their focus shifted to pleasure crafts including both cruisers and sailboats. One of their iconic early boats—a fully restored 1927 26-foot runabout— is on display in the Museum’s California Room.

During WWII they were one of nine local shipbuilding firms that built a variety of vessels for both the Army and Navy. Following the war, Stephens Bros. resumed building stock and custom pleasure crafts for boating enthusiasts both here and abroad. The company closed in 1987 and donated their records and marine architectural drawings to the Haggin creating invaluable research resources for the hundreds of Stephens Bros. boat owners around the globe.

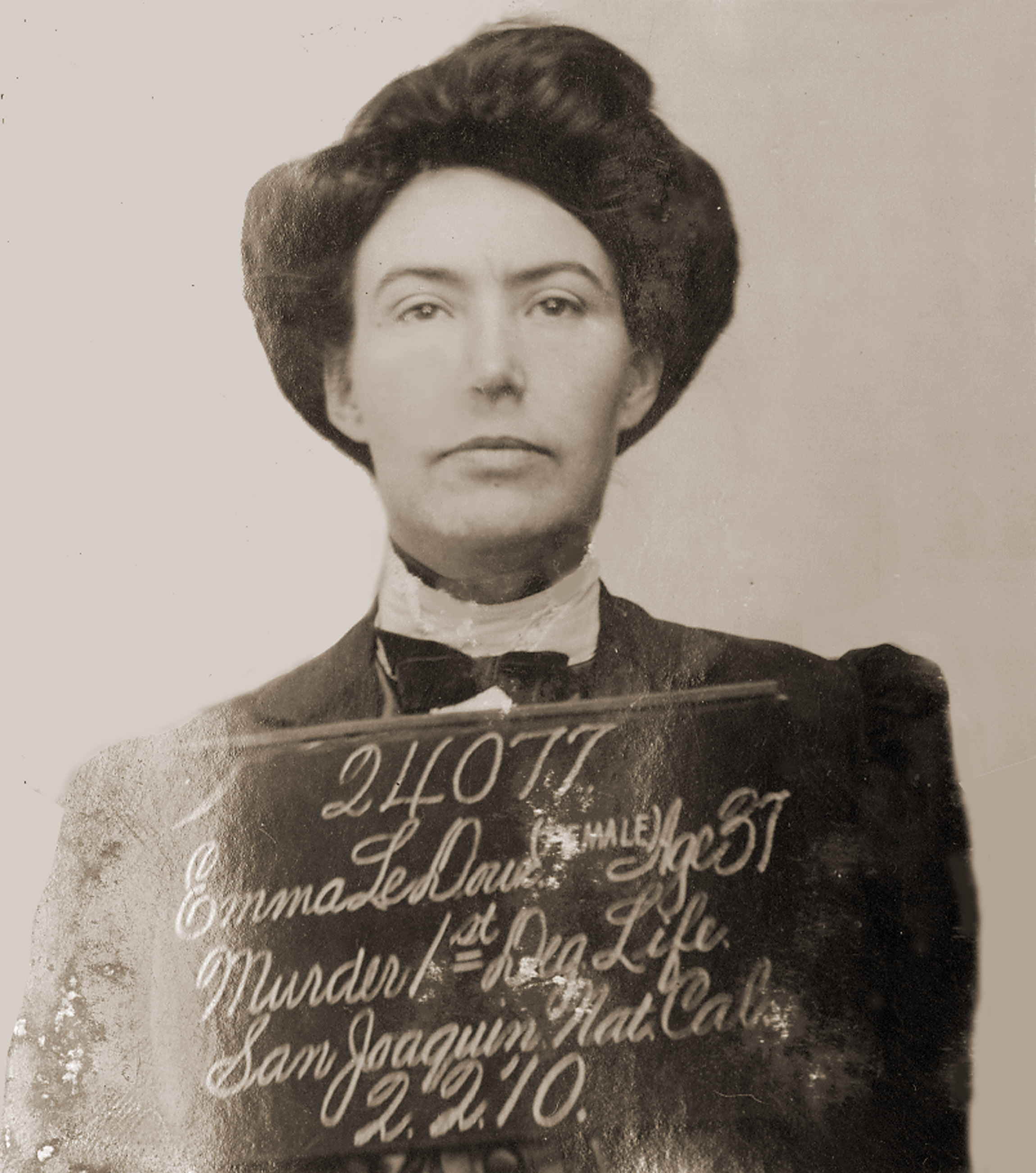

One evening in March 1906, a large trunk was delivered to Stockton’s Southern Pacific railroad depot in route to San Francisco. Employees became suspicious of this peculiar smelling trunk, so police were summoned only to find the lifeless body of Albert McVicar inside. Police traced the trunk to a merchant who had delivered it to the California Hotel for a woman hotel staff believed to be the late Mr. McVicar’s wife.

The woman—whose name was Emma LeDoux—was arrested and details about the grisly crime were splashed across the nation’s newspapers during her trial. Found guilty and sentenced to hang, Emma became the first woman in California to receive the death penalty. She appealed the decision and was eventually paroled, but Emma continued to have run-ins with the law for the remainder of her life. The infamous trunk is on view at the Haggin as a reminder of one of Stockton’s most intriguing court cases.

Once belonging to a pioneer family of San Joaquin County, these period rooms are arranged as they would have been in the 1860s-70s. Anthony and Eliza McGill Hunter, both natives of Ireland, established a grain farm near Linden, California, Their daughter, Jennie, was a successful business woman who attended Stockton Business College and Mills College, and after her father’s death she managed the family’s ranch. These rooms were part of the family’s home until Jennie’s death in 1946 at which time they were donated to the museum.

The Victorian furniture in the four rooms, which include a parlor, back parlor, and two complete bedrooms, dates back over 150 years. Souvenirs from the family’s travels, highly ornamental draperies, and marble fireplaces accent the spaces. Personal touches like family portraits, hand embroidered quilts, hair styling tools, crocheted chamber pot cozies, and vintage sheet music paint a picture of how this middle-class California family lived during the Victorian-era.

“Willy the Jeep” and the entire “Jeep-a-Week” program is a tribute to the people of Stockton and their unique Home Front contributions during World War II. Through a partnership between Stockton High School and the Port of Stockton—the largest vehicle consignment center in the US during the war—the school’s students and faculty set out to raise funds to purchase jeeps for the armed forces.

From January 1943 to September 1945 they raised today’s equivalent of $3 million today to purchase a fleet of 275 jeeps, each bearing a small plaque on its dash acknowledging the school’s contribution and requesting information on the vehicle’s status. Throughout the war, Stockton High received letters from grateful service men and women thanking the school for their support and providing updates on the vehicles. In the late 1970s, one of the Stockton High jeeps found a new home here at the Haggin, and in 2006 “Willy” was restored to his original 1944 glory.

Stockton’s fire fighters’ legacy of service and distinction—from the earliest volunteer brigades to today’s modern Class 1 department—is preserved in the museum’s collection of historic engines, equipment, and photographs on display in our Vehicle Gallery. The helmets, coats, and other gear on display personalize the heroism of the City’s fire fighters, both past and present.

One of the most popular elements of this gallery is the antique steam fire engine affectionately known as “Old Betsy.” It became only the second steam fire engine in California when it was purchased by the Stockton’s Weber Engine Company in 1862. In addition to battling blazes throughout the city, “Old Betsy” was featured in various celebrations such as the completion of the trans-continental railroad in 1869 and the Nation’s Centennial in 1876. It came to the museum in 1931 after being cared for over the years by an association of former volunteer firemen.

While working in a grocery store in New York City, Tillie Weisberg Lewis recognized there was a great demand by Italian immigrants for imported cans of Italian pear-shaped tomatoes, and she began investigating how they might be grown in America. She entered into a partnership with Florindo del Gaizo, an Italian cannery owner who provided her with seeds and canning machinery. In 1935, she persuaded some local farmers to grow the Italian tomatoes and opened the FloTill cannery in Stockton. The Italian tomatoes they introduced are still a staple of American agriculture. In addition to canning whole tomatoes, the company employed Italian-made vacuum pans—like the one on display in the Holt Hall—to produce tomato paste. Over the years, San Joaquin County became the nation’s top tomato producing county, and Lewis—dubbed the “Tomato Queen”—would go on to manage Tillie Lewis Foods, Inc. one of the top five canning operations in the United States.

Victory Park – Stockton

1201 N. Pershing Ave

Stockton, CA 95203

(209) 940-6300

Saturday – Sunday

12:00-5:00 p.m.

Wednesday – Friday

1:30-5:00 p.m.

1st & 3rd Thursday

1:30-9:00 p.m

Join Haggin Museum and become a part of the arts & cultural scene in the Central Valley!

Sign up for our e-newsletter and stay up-to-date on all the exciting exhibitions, events & more!

Copyright 2024 Haggin Museum. All rights reserved.