The Artist and His Model commemorates Jean-Leon Gerome’s completion of a major sculpture, Tanagra, in 1890, and it demonstrates his insistence on working directly from his subject while also attending to compositional harmony. It also reveals his enthusiasm for the art of ancient Greece. The final sculpture held a small version of the Hoop Dancer – the artist’s interpretation of a Tanagra statuette – in her outstretched hand.

Gerome’s precision was legendary, so it is not surprising that he depicted an impeccably tidy studio and presented himself as well-groomed despite the physical labor. The painting itself displays the same love of order; the figures are well centered and bracketed by studio paraphernalia. The unified effect is reinforced by the reverberation of blues, pinks, browns, and whites throughout the painting. In a master stroke of composition, the artist accented the core group against a striking blue wall, yet stopped the stark white statue from coming abruptly forward by placing it behind the pale pink model.

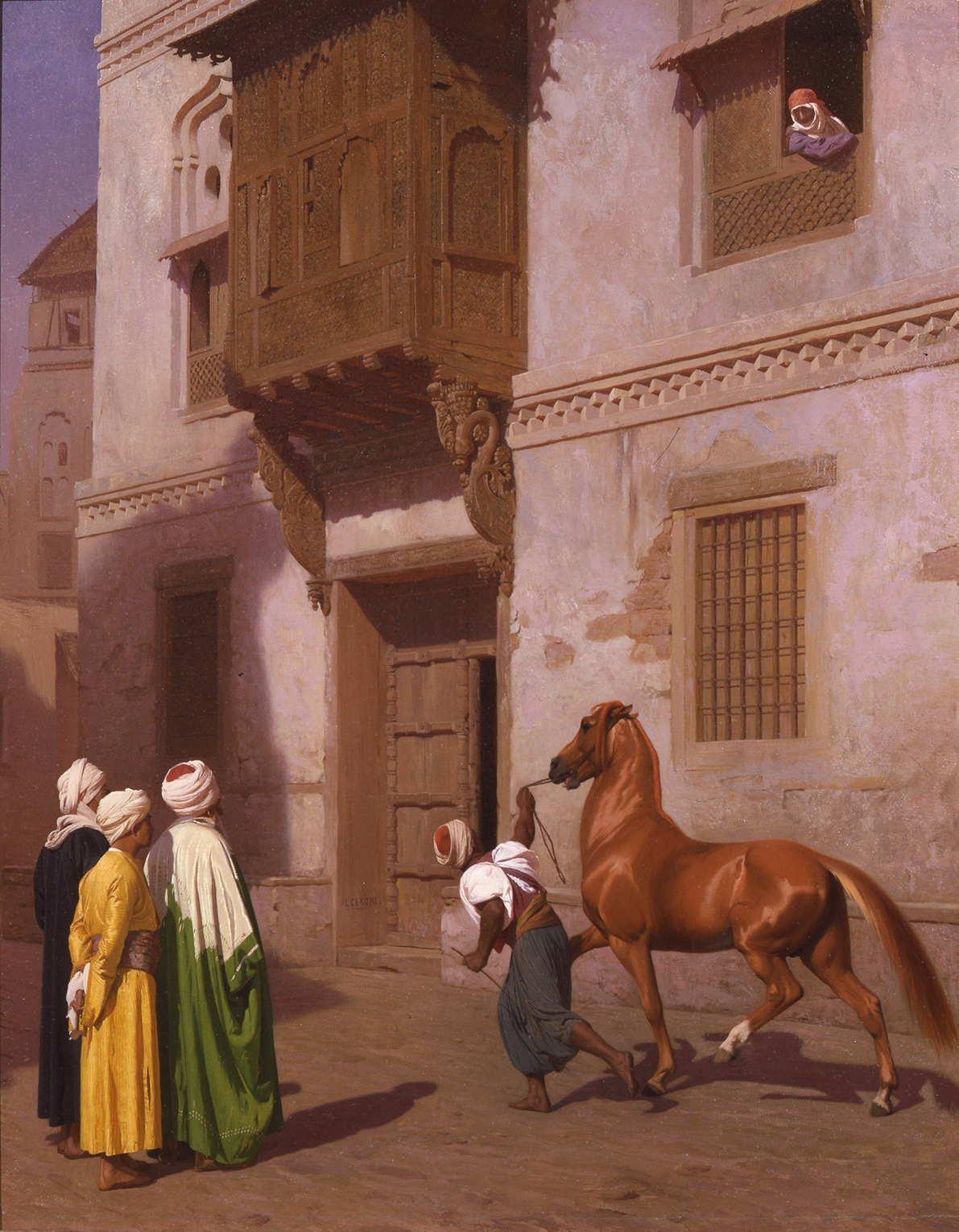

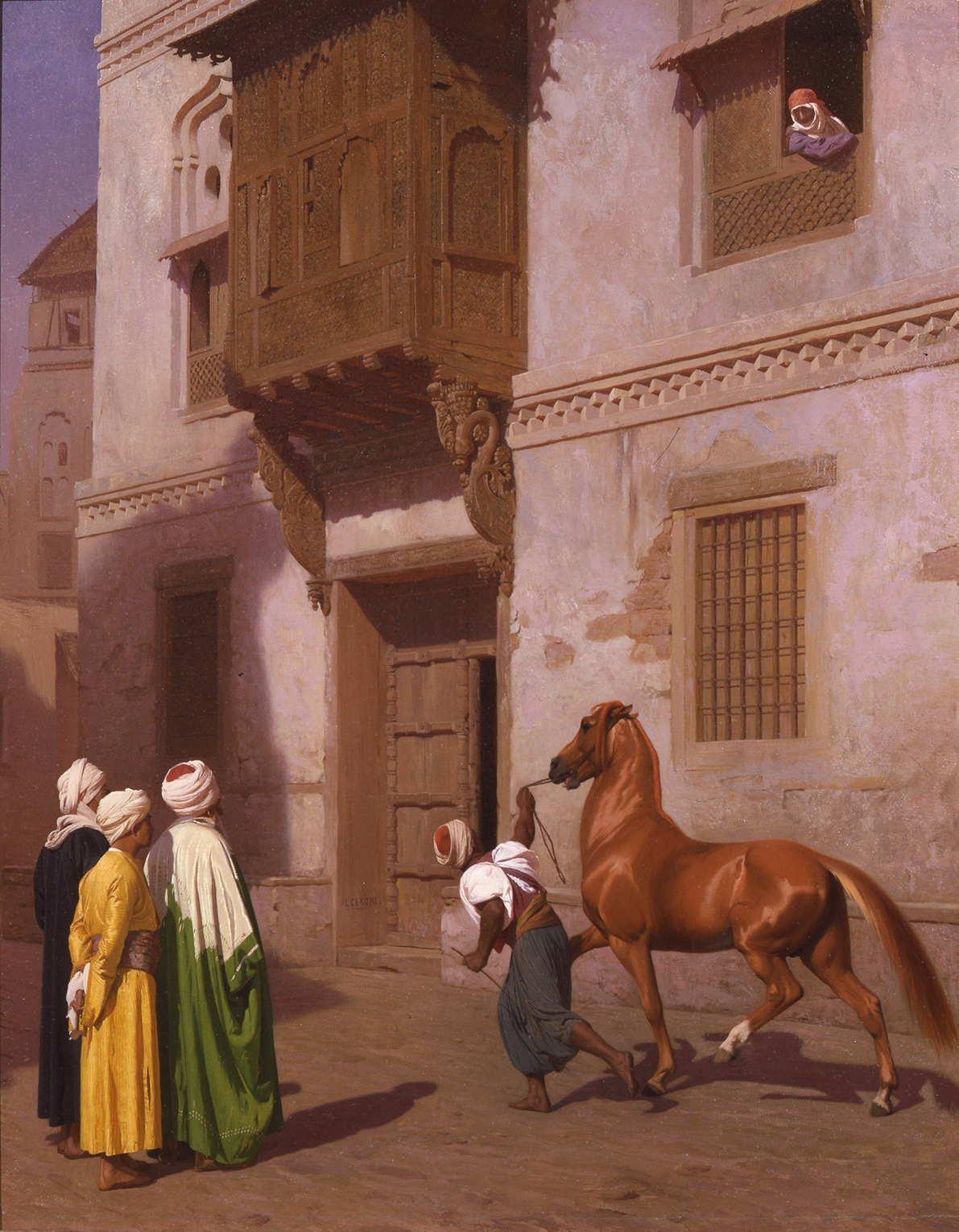

The Horse Market dates from the first decade of Jean-Leon Gerome’s Orientalist subjects and is one of many representations of a commercial transaction, in this case the selling of an elegant chestnut Arabian being trotted out for a prospective buyer. The painting’s details successfully evoke an Eastern setting, yet they are controlled by a carefully constructed composition. Gerome’s keenness of observation is noticeable in the anatomy of the horse and the way the older man’s head sinks heavily between his shoulders, in contrast to the young man behind him.

Gerome’s detailed rendering of costumes and architecture creates an effect of authenticity, but the scene itself is an imaginary construction, since the projecting latticed window of Egyptian style has incongruous Indian or Indonesian supports. He did not usually sketch entire scenes during his travels, only details, which become the basis for compositions worked up in his Paris studio. Despite the inconstant detail, Gerome succeeds in evoking an exotic world.

Over a period of nearly thirty years, Narcisse Virgile Diaz De La Pena painted many views of Fontainebleau Forest, and this is no doubt one of them. The forest interior is so densely overgrown that only a patch of sky is visible, and only filtered sunlight reaches the forest floor. Light is reflected in a pond framed by a spongy carpet of grass. Diaz has used his famous stippled brushwork to suggest the rich texture of foliage, while color separation keeps his tone clear and bright. The final effect is vivid. His forest breathes with vegetal, if not human, life.

Diaz painted so many similar views that it is extremely difficult to date this work with any precision. Most likely it was made after 1848, since it is in his mature style, and since most of his pure landscapes (those without nymphs or exotic women) were done after this time. The very free execution, with modeling little developed, may indicate a work from the artist’s third and final period (c. 1860-1876).

Henry Dasson was a distinguished nineteenth-century Parisian cabinetmaker specializing in gilt-bronze mounted furniture. He began his career as a bronze sculptor, which in turn influenced his technique of chiseling and his bronze work on his furniture.

This ornate clock features a putto, cherub-like child, unraveling a scroll. Dasson’s attention to detail is evident in the well-defined curls in the putto’s hair and the cloth draped over the clock.

Warwick Woodlands is in an area of Orange County, New Jersey, with which Jasper Francis Cropsey was intimately familiar and which he painted often. This landscape is warmed by the autumn tints for which Cropsey was famous. He began painting fall landscapes as early as 1845, possibly under the influence of nineteenth-century poetry and prose as well as the paintings of Thomas Cole.

Fall landscapes became a favorite subject of Cropsey in the 1850s, and he returned to it frequently after his Autumn on the Hudson River and other similar works were acclaimed by London critics in the early 1860s. The basic compositional pattern of that famous painting is reused, with variations, in Warwick Woodlands. In both, a distant view with water, mountains, and a spectacular sunset is framed by rocks and boulders in the foreground. Cropsey overcame the problem of rendering bright colors while still giving an effect of recession by using lively brushwork for these closely viewed features. The cool colors and atmospheric perspective of the distant mountains also help to achieve the desired depth. The horizon recedes like a dream, fading away like the American wilderness that retreats from the encroachment of civilization (implied by the rickety bridge and minuscule figures in the front plane).

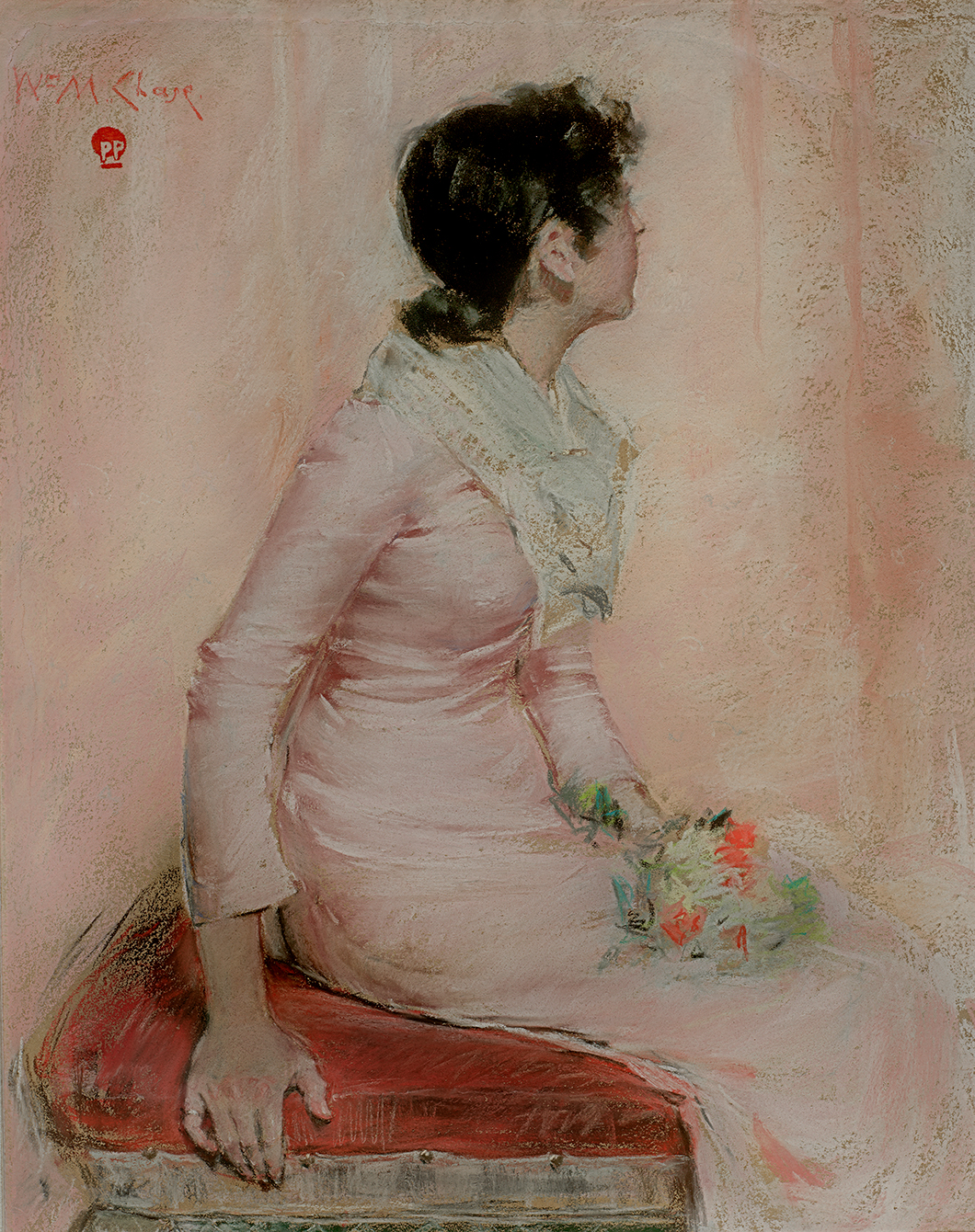

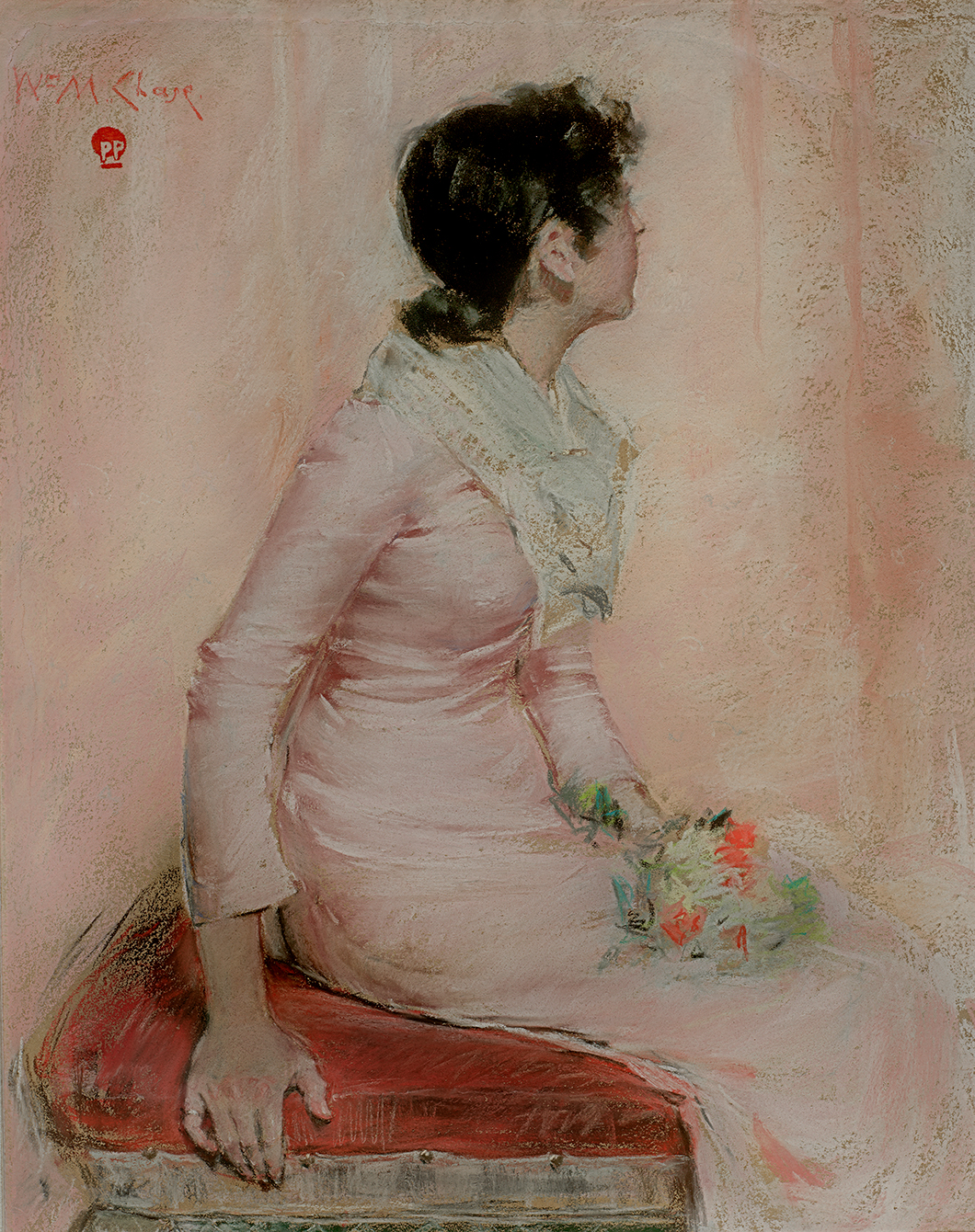

Alice Gerson depicts a genre scene of a woman caught in a leisurely moment of quiet reflection. The sitter glances away in an engaging partial silhouette. The rust colored velvet of the bench she sits on contrasts the vibrant pinks in the background creating visual weight to the scene. Pastel tones and quick brushstrokes accent her femininity. The woman poses with a flower bouquet gingerly placed on her lap, turning her attention away from the viewer in a coy manner. William Merritt Chase’s painting was aptly named for Alice Gerson who became his wife a few years after the work was finished.

Speed of execution was a primary concern to Chase; for him, portraits were to be done in one sitting, landscapes were to be done directly outdoors, and his demonstration nudes were to be completed in a single class. His technique with the pastel medium and bold use of color would go on to influence later generations of artists who were interested in the effects of changing light in nature. Chase had a long and distinguished career and was recognized as the premier American pastel painter working in the late nineteenth century.