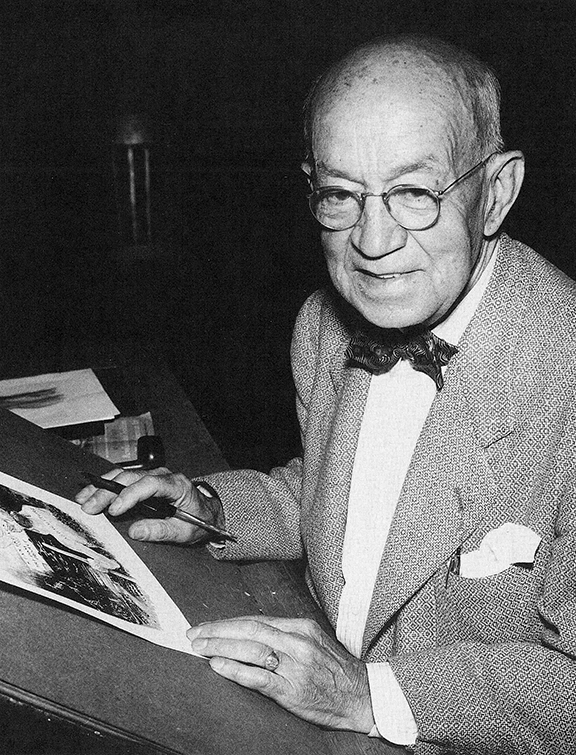

Like many of his generation whose lives bridged the 19th and 20th centuries, Ralph Yardley witnessed many momentous social and technological changes in his world. He bid farewell to the horse and buggy and said “hello” to the automobile and airplane; he listened to the birth of radio and watched the development of television; he looked on as the United States survived the Great Depression and four wars to become a global superpower; and he watched with great interest the growth and changes that time brought to Stockton – his hometown. As an illustrator and newspaper artist for over 50 years, he compiled a remarkable chronicle of his world and a fascinating legacy for succeeding generations.

The son of John and Caroline Yardley, Ralph Oswald Yardley was born in his parents’ home on East Sonora Street on September 2, 1878. His father was a founding partner in the pioneer grocery firm of Hammond, Moore, and Yardley located on Weber Avenue directly across from the old courthouse. Young Yardley attended local grammar schools where his penchant for drawing was first recognized, but it was his design of the title head for the first issue of THE GUARD AND TACKLE – Stockton High School’s official publication – that convinced his parents that he was serious about pursuing an art career.

In 1896 Yardley left Stockton to begin his formal art train ing in San Francisco, first at the Hopkins Art Institute and later at the Partington Art School where he perfected his pen-and-ink technique. One of that school’s instructors, Richard L. Partington, was also an artist for the SAN FRANCISCO EXAMINER and may have helped Yardley secure his first professional position as an artist with that paper in 1898.

At this time, photographs could not be reproduced in newspapers and staff artists provided all illustrations for news stories, feature articles, and editorials. Often accompanying reporters in the field, newspaper artists would execute a quick sketch on the spot or take a photograph from which a drawing would later be made. After about a year of such sketchwork, Yardley tired of these routine assignments.

He returned to Stockton in 1899 and attempted to establish himself as an art instructor and freelance commercial artist. This move proved less than successful and he was soon back in the Bay Area drawing for the SAN FRAN CISCO CHRONICLE. It was not long before Yardley once again felt stifled by the mundane work he was given at the CHRONICLE; and in 1900, he sailed for Hawaii to become the staff artist for the PACIFIC COMMERCIAL ADVER TISER (later to become the HONOLULU ADVERTISER).

It was in Hawaii that Yardley was given his first real opportunity to develop and express himself as an artist. Soon he was providing three and four drawings an issue, including special column headings, portrait work and, for the first time, political cartoons. Often published in conjunction with the firey editorials by the ADVERTISER’S editor, Walter Giffard Smith, Yardley’s “pen-point” attacks were directed against the courts, the clergy, prohibitionists, and politicians. Many of these cartoons elicited howls of protest from the offended parties and one even resulted in a mistrial of a criminal case along with a contempt of court citation and a jail sentence for Smith. By the time he returned to the mainland in 1902, Yardley had established himself as one of the more promising young newspaper artists on the West Coast.

He settled again in the Bay Area and worked alternately for the SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE and the SAN FRANCISCO BULLETIN. In addition to his regular sketches for news articles and an occasional political cartoon, Yardley also began to draw sports cartoons and comic strips. It was during this time that Yardley became good friends with two of his co-workers – Thomas Aloysius Dorgan “TAD” and Rube Goldberg – both of whom went on to become renowned cartoonists. New York City was generally regarded as the best location for aspiring newspaper artists to advance their careers; and with that in mind, all three friends eventually moved there in 1905.

For two years Yardley worked as a member of the NEW YORK GLOBE’s art staff; but unlike TAD and Goldberg who remained in New York, Yardley once again returned to the Bay Area, this time to accept the position as head of the SAN FRANCISCO CALL’s art department. From 1907 through 1909, Yardley worked for the CALL; and during that time, his most interesting work was for the paper’s Sunday Magazine section. Published in full color and often covering the entire page, these illustrations featured beautiful women in seasonal activities. Viewing Yardley’s artwork from this period, it is evident that while in New York City he had paid considerable attention to the works of the leading illustrators of the day, including Charles Dana Gibson, James Montgomery Flagg, Howard Chandler Christy, and J. C. Leyendecker.

With the impressive work he had done for the CALL added to his portfolio,-Yardley set out again for New York – but this time as a free-lance illustrator. For almost three years, he specialized in cover art for national periodicals such as HARPER’s and, LESLIE’s, and gained some attention for a series of novelty postcards. His East Coast sojourn came to an end when after learning of his father’s health problems, he returned to Stockton.

Back in his hometown, Yardley continued free-lance work, occasionally providing the STOCKTON RECORD and other local publications with material, doing advertising art, and specialized work for various civic and social organizations. His “Girls of Stockton” calendars, featuring comely young ladies and Stockton vignettes, were quite popular as well. With the outbreak of the First World War, Yardley – like so many other fellow artists – used his talents to help aid the national war effort. Throughout 1917 and 1918, he produced a series of posters and cartoons that promoted the various Liberty Loan campaigns, several of which won him national recognition in federally sponsored competitions.

After the signing of the Armistice, San Francisco once again lured Yardley away from Stockton, and from 1919 through 1921 he drew political cartoons for the BULLETIN and continued to accept free-lance commissions. While working in San Francisco, he married Carmen Glauch in April of 1919; and two years later their first daughter, Patricia Ann, was born. It was also about this time that he received a job offer that would affect his life for the next three decades.

The STOCKTON RECORD had always been impressed with Yardley’s work; and in late 1921, the paper was in the position to offer Yardley permanent employment. A new wife and daughter coupled with family and social ties to Stockton as well as what was reported to be “splendid financial inducements” of the RECORD proved to be the winning combination in extinguishing the wanderlust in Yardley. In January of 1922, he began his 30-year tenure with the STOCKTON RECORD as its resident artist.

Yardley’s duties included a daily editorial cartoon and special layouts such as the “Out-O-Doors” section published every Saturday to promote automobile travel throughout the West. (It was not surprising that major advertisers in this particular section were local automobile dealers.) Because he was also an excellent photographer, many of the photos, as well as the artwork, were Yardley’s handiwork. Another feature that appeared every Saturday for many years was a series of caricatures of local personalities, sports figures, and National Park personnel. Yardley continued to receive national attention, with many of his car toons being republished by other newspapers and the LITERARY DIGEST. In 1937 Yardley’s cartoons were among those featured in an exhibition at the Huntington Library and Arts Gallery in San Marino, California.

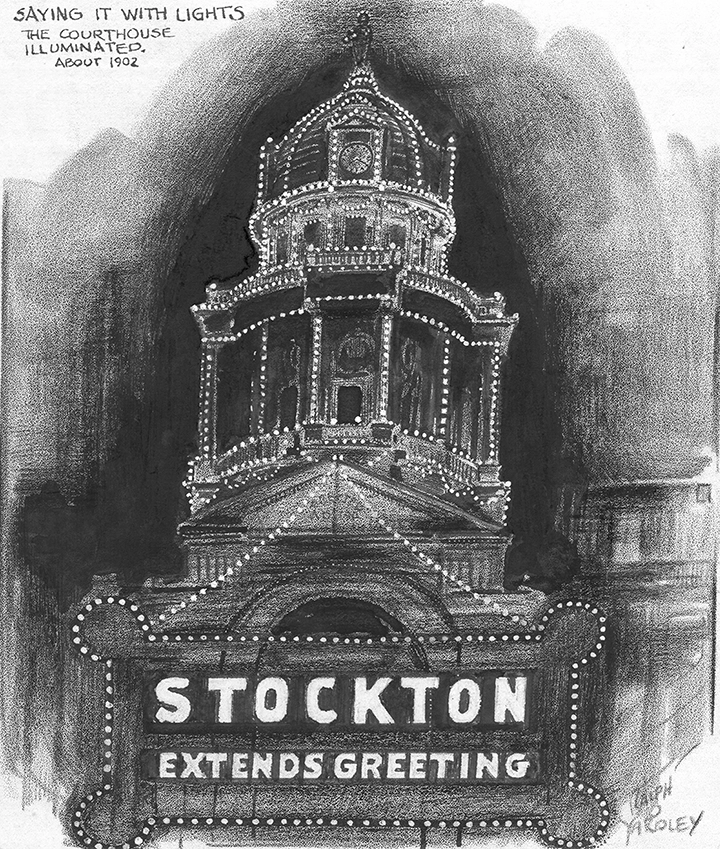

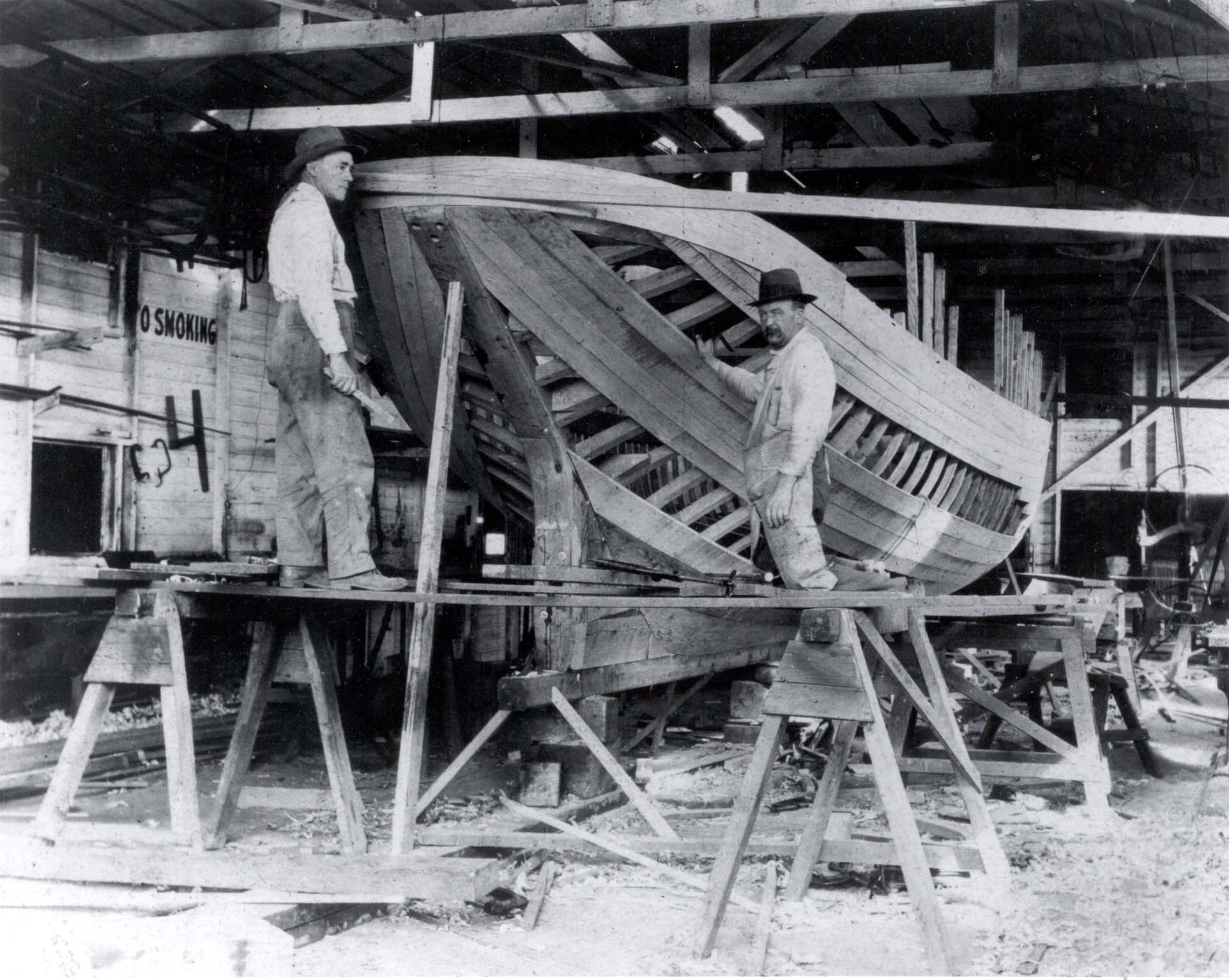

RECORD readers soon became familiar with Yardley’s distinctive style. Using “Coquille board,” a drawing paper with a lightly “pebbled” surface, he would combine the delicate lines of the pen for detail with the bolder strokes of his pencil or crayon for the richly shaded areas. Nowhere was Yardley’s talent more evident than in his most popular contribution to the RECORD – his “DO YOU REMEMBER?” series.

Published every Monday beginning in November of 1924, these illustrations/ cartoons highlighted people, places, and events from Stockton’s past. Working from old photographs and his own memories, Yardley would create nostalgic and highly detailed glimpses of the city’s bygone days, often with humorous touches so characteristic of the artist. Taken as a group, these drawings serve as a wonderful visual history of Stockton and reflect the love that Yardley had for his hometown. Avery Kizer, the long-time editorial writer for the RECORD who worked with Yardley for a number of years, remembers that the artist would sometimes have great difficulty coming up with a suitable idea for a cartoon to accompany the paper’s lead editorial. Kizer goes on to stress that nobody had to help him with ideas for “DO YOU REMEMBER?” So popular were these drawings, that years after Yardley’s retirement, the RECORD republished the series on a daily basis from 1966 through 1969. (In 1970 the STOCKTON RECORD donated almost 1,000 of the “DO YOU REMEMBER?” drawings to The Haggin Museum. This represents the largest single collection of original Yardley artwork in existence.)

Yardley was first and foremost a newspaperman, but he always took time to be a father. His second daughter, Maryjane, was born in 1925 and both she and Patty soon became the subjects for his artistic energy. Yardley pictured his daughters’ images in plaster, on canvas, and in hundreds of photographs. He was also fond of drawing giant Easter bunnies, jack-a-lanterns, and Santa Clauses that the girls would take to school, much to the obvious delight of their classmates and teachers. Although Yardley and his wife separated in the late 1930s, he and his daughters maintained their special relationship.

Yardley retired from the RECORD in 1952, just shy of his 74th birthday. He spent the remainder of his years either in the Stockton home of his sister, Caroline Moore, or in the Carmel home of another sister, Emily Yardley. His interest in art never really diminished and he occasionally painted landscapes or doodled for his grandchildren. Gradually his health declined and on December 6, 1961, Yardley passed away in the town where he had been born 83 years before.

Yardley was once asked why he had ever taken up drawing as a profession. He replied, “At a very early age, I began itching for something and have been scratching with pen, pencil, and brush ever since,” It is indeed fortunate that Yardley was so “afflicted,” for his many “scratchings” have captured and preserved for us the mood and tenor of an earlier time. Even though Yardley has been gone for over 25 years, his illustrations and cartoons help to keep his unique sense of artistry, creativity, and humor both alive and vibrant.