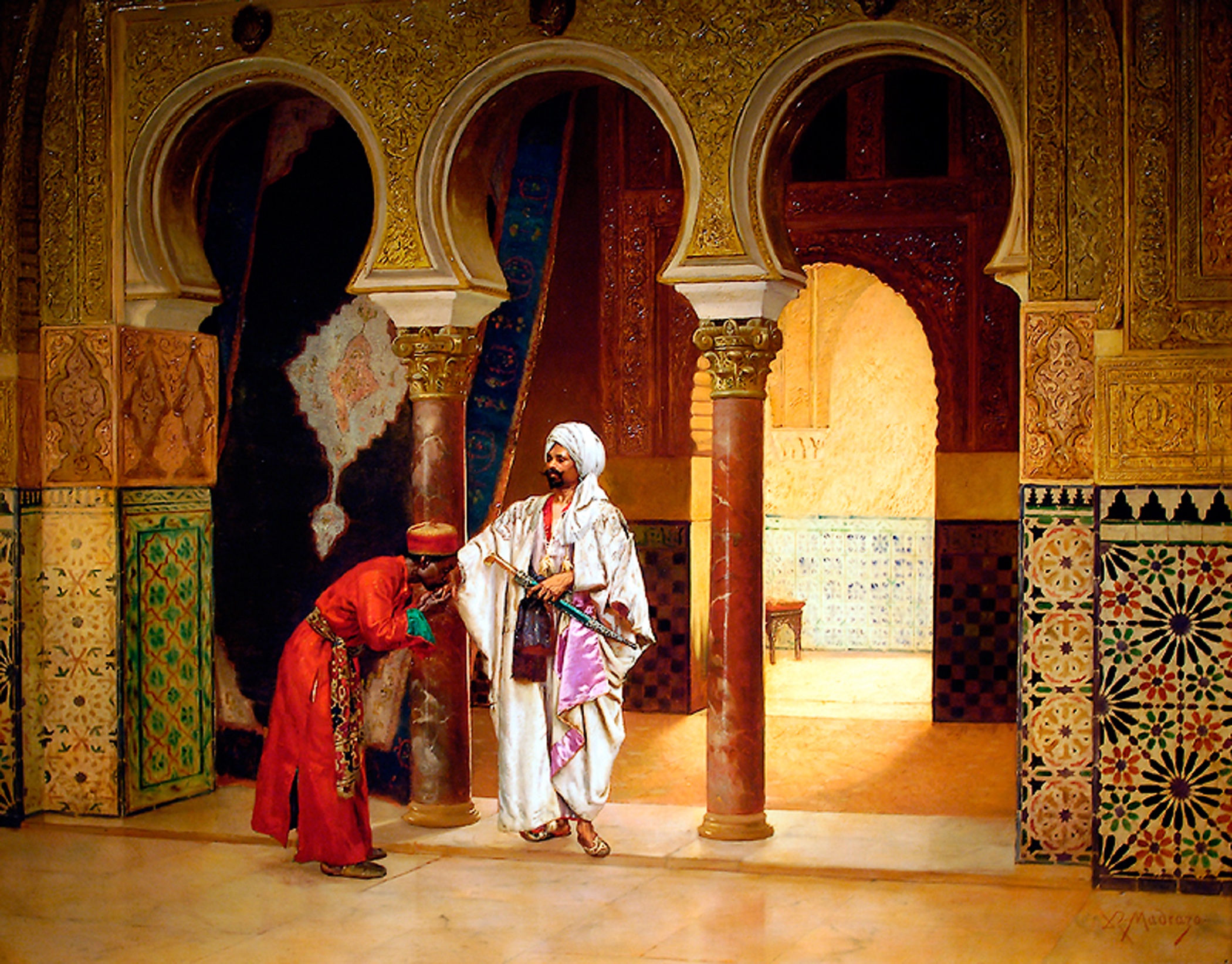

An Interior of Alcazar, Seville

Unknown Artist

Collections

An Interior of Alcazar, Seville

By René de Saint-Marceaux (French, 1845-1915)

De Madrazo came from a Spanish family of painters. His father, Federico, was his earliest teacher. He studied at the Royal Academy in Madrid and, after 1862, in Paris with the artist Léon Cogniet. De Madrazo exhibited regularly in the Paris Salon, winning a medal at the 1878 Universal Exposition. With his brother-in-law Mariano Fortuny, he embraced genre painting, turning out small, elegant paintings of beautiful women in sumptuous surroundings. In 1882, he and his friends—the artists Giuseppe de Nittis (1846-1884) and Alfred Stevens, and the gallery owner Georges Petit—co-founded the Exposition International de Peinture to gain more exposure for foreign artists working in Paris.

In the 1890s, de Madrazo traveled to New York and remained there for several years. He continued his acquaintance with the Haggins; when he remarried in 1899, he sent Louis and Blanche an announcement. De Madrazo’s portraits were popular in New York Society. He painted industrialist Cornelius Vanderbilt II, Gertrude Vanderbilt, and collector Archer Milton Huntington, among other luminaries.

Les Désguisés depicts two ethereal female figures rendered in an elegant fashion. Their ghostly appearances intensify the stylized nature of their poses, and muted pinks, soft grays, and electric blues add a dreamlike quality to the painting. There is also a hint of playfulness at work here, for example, in the way that Laurencin paints flower bouquets into elaborate headdresses for the women—one embellished with an actual bird atop.

Marie Laurencin became part of the Paris avant garde scene of the 1920s. She developed a style that was similar to early Cubist works with their shallow sense of space and flat planes of color. Wistful young women and animals loosely painted in pastel hues, like those seen here, were subjects she returned to many times.

The Golden Pool presents a view of a hazy sun as it begins to disappear behind the horizon of a French countryside. Leon Richet captures a panoramic reflection of the dwindling sunlight and cloudy sky with airy brushstrokes and hints of green, brown and yellow to indicate texture. Overgrown shrubbery and towering, shadowy trees provide an imposing focal point and contrast to the abandoned canoe left at the shore of the secluded marsh. As the light reflects on the water with its abundance of lily pads, there is a feeling of tranquility and serenity within this untamed wilderness.

Richet, like many of his fellow artists in the Barbizon School, eagerly left their bustling studios situated in the city in favor of the transcendent majesty of the Fontainebleau Forest and small rural areas outside of Paris. Rich terrains, like the one seen here, became a sanctuary for these artists to fully experience nature. It was this movement that led to the recognition of landscapes as their own independent subject matter- a theme that was later explored by the French and American Impressionists.

Here Jules Worms re-creates a Spanish street as it might have appeared in the time of Goya. The background is based on a watercolor sketch the artist made during an 1877 visit to Salamanca. The picturesque setting forms a backdrop for a farce.

As so often in Worm’s work, love is at the heart of the comedy, in this case an old story told long before by Goya, and more recently by Fortuny: a mismatch of a pretty young woman and her old but presumably wealthy husband. Worms shows a predictable outcome. The beautiful maja, wishing a rendezvous with her young lover, has dropped her fan, which her husband politely recovers. His work is a comic-opera version of old Spain, in which every young woman is attractive, every young man dashing and handsome, and every husband a buffoon.

Like other Realists of the nineteenth century, Monchablon was inspired by the example of the seventeenth-century Dutch artists. The year he began to paint landscapes, he traveled to the Netherlands. Although his landscapes have a decidedly modern look, they share certain features with Dutch works, such as low horizons giving prominence to skies, broad, panoramic views, and painstaking detail.

This painting features the similar flat geography that often appears in Monchablon’s works. The vast sky is mostly clear with a few feathery clouds floating throughout. The golden foreground and curves of the Saone draw the viewer’s eyes toward the horizon. In the distance harvesters can be seen tending to the fields.

Like the boulevards of Paris, London’s Hyde Park was the place to see and be seen. De Nittis interpreted this urban landscape with loose brushwork in the Impressionist style. The deeply shadowed foreground is balanced by brilliant sunlight that provides a high contrast burst of energy.

De Nittis enjoyed the good life. His filled his Paris apartment with friends like artists Edgar Degas and Edouard Manet and fed them lasagna, a specialty from his home in Naples. De Nittis influenced William Merritt Chase and perhaps inspired Louis Terah Haggin to purchase this painting as a reminder of when he lived in England.

This painting was a focal point in the National Academy of Design Annual Exhibition in New York and was highly praised by art critics. George Inness’ exhibits were lauded for both their truthfulness to nature and poetry, while his spontaneous brushwork and luminosity were reminiscent of the Barbizon painters.

The color and composition of Old Homestead show how Inness’ painting methods had changed since painting Juniata River. Color harmony, a strong point of his later work, is achieved by restricting the range of values and by making green the predominate color. Since he had eliminated contrived curves and framing devices, the painting seems more casual and open.

The rolling landscape is conceived here as a series of roughly horizontal strips, a demonstration of his belief that a composition ought to be organized into three great planes. With such an arrangement, whatever rises above the horizon is given emphasis—in this case the magnificent elm trees just right of the center.